Homo Ludens

2016 / Rome

By CHRISTOPH SEHL

The most frustrating thing about the spectacle (in Guy Debord’s sense of the term) is that it cannot be betrayed or deceived; the spectacle deceives and betrays us. A psychoanalyst once described the problem as an interactive ambivalence, in as much as we criticise power while forgetting our identity with it. In here lies the difficulty of handling the evaluation of several perspectives on a single object, or maybe the difficulty of coming to terms with paradoxes.

At the end of 2015 a remarkable show was held at Galleria Magazzino in Rome, titled ‘homo ludens’; an exhibition of artworks by Arina Endo and Gianluca Malgeri. They met in early 2015 and did a first exhibition, ‘Edge of Chaos’. Their cooperation appears as a wonderful coincidence and their artworks are a correlation in the best sense. Consequently, they came up with the ideas of ‘homo ludens’ revolving around the figure of Pinocchio.

At first glance we might find in ‘homo ludens’ a common art exhibition in which the title presents a metaphor for the status of artists in a more or less wide context with the term ‘homo ludens’ referring to several cultural theories in which the position of art in society is well defined. And in some respects, such assumptions are not entirely wrong. Endo and Malgeri had engaged in a similar approach while doing artistic research on their surroundings, particularly their Berlin environment - to do whatever they wanted to do plus an additional insignificance, or in other words, agony. But ‘homo ludens’ went one step further through inverting the gaze...

The effect of changing the point of view is not only to obtain a different perspective on the same phenomenon, rather to receive a different thing. That is to say, it is not about technically changing ones location in space for adding certain quantitative, geometrical, measurable, aspects. In this sense, doing an installation which reflects on childhood would be tantamount to inventing childhood, i.e. the classical method of othering. As such, othering is a kind of projection far from what the thing itself is. However, seen differently changing the point of view can alter things in their quality.

Through stepping outside permanent self-referentiality, one can reinvent the ways of acting beyond convention, bias and prejudice.

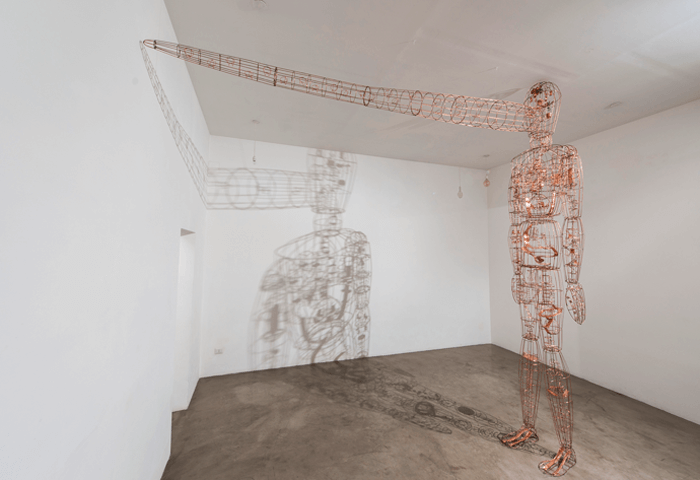

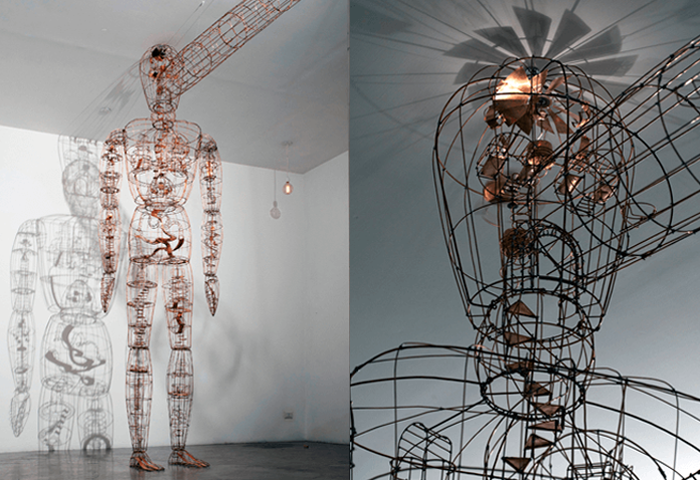

Through his work ‘homo ludens’ Gianluca Malgeri shows us the possibility of a radical shifting between different standpoints as well as the possibility of a standpoint itself. The huge statue of Pinocchio is built with soldered copper. Like a see-through lattice work, we can see the backside of the figure and what lies behind it. Inside the body - inside the limbs, belly or the head - Malgeri has constructed an scattered world of stairs, carousels, spiral slides, jungle gyms and seesaws: the anatomy of Pinocchio is a playground, the ‘land of toys’ - a promised utopia of good but failed good deeds.

The most remarkable part of the sculpture is the nose, the famous nose of Pinocchio. In Carlo Collodi’s novel, the wooden nose grows every time Pinocchio lies. ‘... the disappearance of the nose is the moment of his surrender to obedience’, writes Carmelo Bene as quoted by Gianluca Malgeri. At one point in his discussion of Pinocchio, Bene chops the nose off. This was his special way of alluding to the social order. Malgeri now reverses this. He exaggerates the nose, builds an oversized version: it is as big as the whole body. Here, we go beyond obedience, and the social order is cancelled. We find Pinocchio on the other side of the border and see him as the ‘heroic refusal of growing up’ (Bene). He is not gentle or handsome; he is beyond the idea of naïveté and juvenility; he is not the object of education anymore; he is the evil child whose possibility we always try to ignore. At least, this Pinocchio is a rebellion against the adult point of view, against social order, against power - maybe a way of going beyond the ‘spectacle’.

Through opening up this playground Malgeri produces a wonderful metaphor for the verycomplicated way of thinking in other heads and for the evaluation of the simultaneity and contrariety of different perspectives. We can find ways for refusing to belong to a single idea and a single culture. We can combine two or more things not rationally connected in the logic of the social order. Hence, the switch is not only from one perspective to another; it is from one to many.

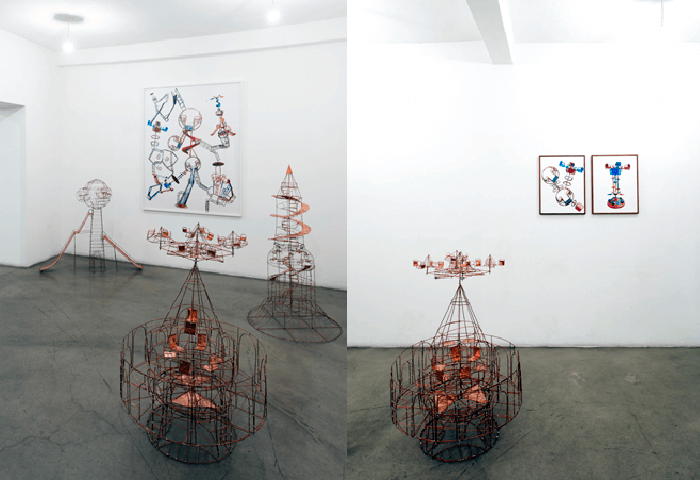

This, he works out in several sculptures in soldered copper and in prints that combine the motifs of playground in montaged images. The parts are not ordered logically, as rationality would have it. They are built one into the other; we are confronted with complex structures which cannot be assembled and made into a single totality. ‘Homo ludens’ means a kind of self-conception of a world where the construction of the gaze cannot escape self-evidence or the social order. However, it is not a direct disobedience either, it is the turning of the gaze within dispersion and in the aftermaths of plurality.

It would be too easy to suggest that this ‘land of toys’ is the end of history or one can find the ultimate goal in it. Malgeri and Endo are aware of this in as much as they know what agony means. This is because they come from the world of endless playing, the ‘land of toys’; it is because they have done this paradoxical reflection on artist’s life.

Endo constructs a small sculpture – City of Dice. It consists of a shelf attached to the wall and covered with a layer of sand. On the sand, she places a pile of handmade, rigged, loamdices. The whole thing is very small. It is a projected image of a city, an oasis in the midst of desert, maybe a fata morgana, a mirage – beyond judging whether it is desirable or not, itself a deceit bringing together cause and effect. It is also the world of all random things heaped on us: tomorrow the throw of dice is different. It is an image of our sophisticated prison in which possibilities seem endless and limited at the same time. In this sense, Malgeri’s subject – Pinocchio – is the beginning of projecting the multitude of perspectives and the necessity of discussing their continuation. He builds up arguments, theses. His Pinocchio produces an endless number of them. We can never reproduce a view on this sculpture identical to our previous. The installed formal multiplicity aims at denying social, political and historical representation.

‘Homo ludens’ is bound to a double-minded structure. Inside,there is the definition of the body internalising the ‘land of toys’; on the outside, a nose growing to an enormous size. Either way, the borderlines remain unclear. Although Pinocchio is lying, the ‘land of toys’ cannot be taken from him. An incomprehensible reality turns real.

If we now remove wishes and desires from Pinocchio’s thinking in order to make him a normal human being with flesh and bone, the different perspectives would be flattened down. If we enter the spectacle through the backdoor we realise there is no way out and the status of this prison shifts from a matter of fact to a state of mind (‘The City of Dice’).This means we can act directly with ideology – not only with the surfaces of power.

All in all one must not claim that the place of artist within society is that of person who affirms and lies at the same time. This would be too simplistic. Arina Endos and Malgeri’s concept of Pinocchio indicates this continual contradiction through creation of exquisite artworks.