Apollo and Daphne

2009 / Berlin

Rules of the Game

by James Bae

Myths endure as much for their improbability to attain reasonable truths as they do for the arcing idealism they represent.It comes as no surprise, then, that the majority of archetypes that still hold resonance over us still are necessarily themost basic ones: heroic action and unrequited love. In this light, Apollo and Daphne is as close to a problem-play aGreek myth can be, being neither overtly heroic nor wholly tragic in its narrative. Incited by the sanctimonious whim of Eros, the attraction necessarily was inauthentic; Apollo’s affections nor Daphne’s disdain were never self-realized events. Whether shot by lead or infected by aurum, it’s not a matter, then, of who is chasing whom, but as it is for exactly what?

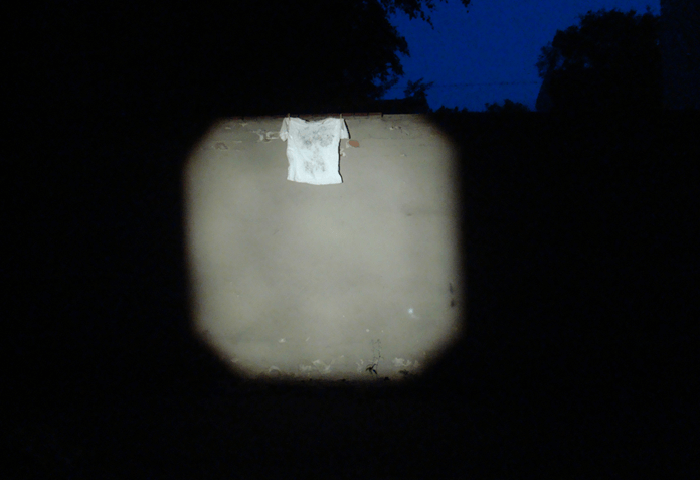

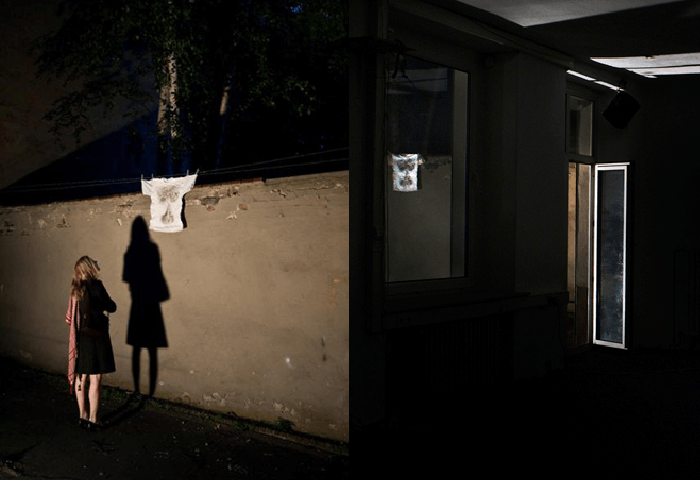

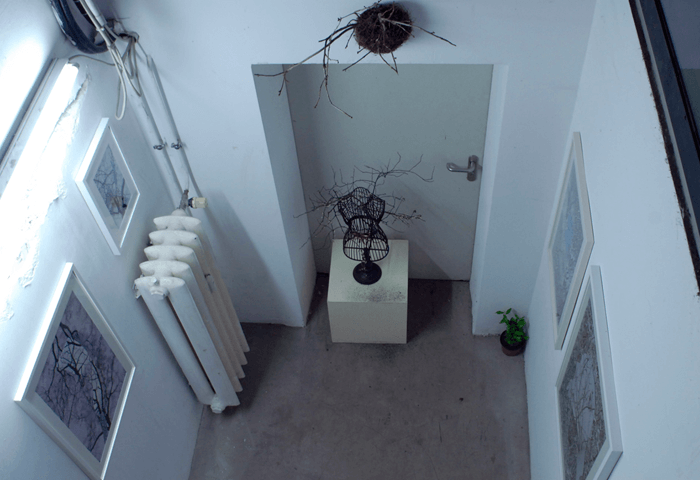

Malgeri depicts this romantic parlor game in brief, sedentary gestures: a hair-specked shirt, a dress mannequin, a passelof branches. They stand in quiet semaphore to one another, suggesting a certain universal futility: there is nothing to bedone. It is in the tacit strangeness of these assemblages in each other’s proximity that the myth becomes inwardlyaccessible. A male figure fails to achieve emotional validity to a female, his pride limp as the ruefully pathetic white shirtthat represents him. And, in an inversion of authority, the statuesque figuration of Daphne, as an industrial clotheshorse,underpins the myth’s main conceit: there is nothing more sincere than authenticity of disinterest. It is through suchreverse pneuma that a heart sublimates into steel, and branches suggest antlers and the quibbling fear of being, simply,another trophy on the wall. Relying upon these simplest of allusions, the imaginative and the irreal create a physicalconduit in Malgeri’s work where personal narrative can take form.

Freud, who suffered immeasurably under the weight of Shakespeare’s long shadows, summarized influence as this: Welove authority, but authority is not obligated to love us in return. The steel Daphne, like a fictive tower, is a metaphorthat cannot be easily translated into words - or would want so. At times, things are deontically what they are; and nomore. To make more of things, Malgeri hints, is classically Apollonian, serving only to reify the very scope of one’s owninitial argument. Like a bombed night at a bar, or a particularly bad row with a future ex, one is left with the sorrowfulcomfort that this is, as moral critic Bernard Williams suggested, all just a matter of moral luck; one is fully thrown intothe torsion of events sometimes besides our best wishes. Perhaps, one simply just might be too tired to fuck. So one canlook at these works as wan monuments to emotional failure or chi ama, crede, however they so wish;as long as onerealizes there is all or nothing to be done by doing so.